Eminent Atlanta Victorians

John Calvin Peck

This is the first in a series of short biographies of Eminent Atlanta Victorians -- not the overdone politicians or Confederate generals but those who made significant, but often forgotten, contributions to the city, state or region in business or the arts. I will try to link these individuals to specific places, monuments, buildings or grave sites so that those who wish to make a direct connection with the long dead can search out those "artifacts."

Peck was born in Sharon, Connecticut in 1830 and was educated in the public schools and the nearby Watertown Academy where he reportedly excelled in both the sciences and literature. Following school, he trained as a carpenter and worked in upstate New York before returning to Connecticut as a carpenter/contractor. Because of asthma, he eventually moved south in the 1850s, settling in Knoxville, Tennessee and finally taking up permanent residence in Atlanta in 1858. He worked in his new hometown with the already established antebellum builder/architect, John Boutelle.

Boutelle was a fellow New Englander [born in Massachusetts in 1814] who had come to Atlanta in 1852 after moving south for health reasons. Mainly a contractor, he designed many buildings in the antebellum period and even listed himself as an architect in the 1859 Atlanta city directory. His buildings included the Atlanta Medical College, Collier Building, his own home and those of early Atlanta leaders like Austen Leyden and John Neal. J. C. Peck and Boutelle had much in common and it was stated in the former's 1908 obituary that Peck "rose rapidly in the gentleman's [Boutelle] esteem, and was soon placed in a responsible, lucrative position." (2)

Like many northern-born men in nineteenth century Atlanta, the Civil War placed Peck and his growing family [he had married New Yorker Frances Josephine Hoyt in 1853 before moving south] in a tenuous position. Many of them like engineer and entrepreneur Lemuel P. Grant and architect Calvin Fay became actively and directly involved with the Confederate war effort. Fay became a captain of artillery and Grant oversaw the construction of Atlanta's defensive works. Peck's mentor and employer, John Boutelle, also worked on the city's defenses. At age thirty-one when the war began, Peck avoided active service [perhaps his asthma was a factor?] by working to supply war materials for the military. Georgia governor Joseph E. Brown commissioned him to make pikes for the state militia and he also attempted to start a business producing rifles, which failed. "Joe Brown's Pikes" were described as "a sharp, heavy steel blade firmly fixed in a wooden handle, and jumping into place by use of an ingenious spring." The rifles were made by hand by Peck himself and shot a bullet "one inch in diameter and two and one-quarter inches long." In addition, Peck also served briefly as superintendent of woodwork at the Atlanta Arsenal.

As the war dragged on, Peck's health suffered once again due to his asthma and he moved to Thomasville, Georgia. Somehow he managed to extricate himself from war-torn Georgia by taking his family north to Minnesota where they remained until the end of the war. (3)

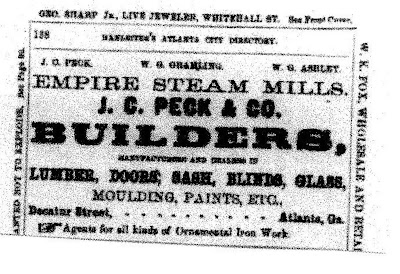

Shortly after the end of hostilities in 1865, John Calvin Peck returned to the burnt out ruins of Atlanta where he established his planing mill on Decatur Street and then N. Loyd (Central), just steps from the train and freight depots in the heart of the city. By the mid-1870s, the success of J. C. Peck and Co. supplying

| ||

| Atlanta City Directory 1870 |

lumber and making sashes, doors and windows was clear. The owner was listed as one of the city's wealthiest men in 1876 and was a much sought after contractor for many major buildings. He oversaw the construction of the new state capitol [originally the Kimball Opera House], the massive Kimball House

|

| First Kimball House Hotel |

|

| Old State Capitol, Marietta St. |

The solidification of his preeminence as Atlanta's foremost building contractor came in the 1880s. In 1881, he was a stockholder in the International Cotton Exposition. Not only was he an investor, but he also served on the Executive Committee as well as Chief of Construction and Superintendent of Construction.

|

| U.S. Customs House, Marietta St. |

|

| Markham House Hotel |

Peck would later serve in similar positions for the Piedmont Exposition of 1887 and was an organizer of the Atlanta Cotton Factory and Fulton County Spinning Mills. Finally, he was actively involved in the construction work of the 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition. (5)

|

| Main Building, International Cotton Exposition 1881 |

Although John Calvin Peck spend his last fifty years in the South and was considered a Pioneer Citizen of Atlanta, he retained at least one very visible part of his New England heritage. He was a founder of Atlanta's Unitarian Church of Our Father in the 1880s and remained active in this organization until his death, serving as president of the congregation as well as chairman of the board of trustees at various times. (6) It seems very likely that he supplied the wood and contracting for the 1883 church building which was built near his long time home at 83 Ivy Street [between Wheat and Houston streets]. (7)

|

| Church of Our Father, circa 1884. Courtesy of the Atlanta History Center Archives. |

When John Calvin Peck died, the list of pallbearers and "honorary escorts" read like a Who's Who of prominent Atlantans. They included M. O. Markham, Frank Rice, George Winship, Joseph Hirsch, Samuel Inman and R. J. Lowery. (8) Peck was interred in an impressive mausoleum on the north end of the high ridge bisecting the oldest part of Oakland Cemetery. For any "graveyard tourists" who wish to visit the mausoleum, be sure to note the beautiful stained glass window with the entwined initials of John Calvin Peck.

|

| J. C. Peck Mauseoleum, Oakland Cemetery. Author's photo. |

|

| J. C. Peck initials inside the tomb. Author's photo. |

_______________

Footnote abbreviations for this article are as follows: ACD, Atlanta City Directory [followed by the date]; AC, Atlanta Constitution; AJ, Atlanta Journal.

(1) There are many excellent contemporary descriptions of Atlanta in the months immediately after the Civil War when men like John C. Peck returned. Some of the better ones are used here. J. T. Trowbridge, The South: A Tour of Its Battlefields and Ruined Cities (New York: Arno Press, 1969 -- originally published in 1866), pp. 460 and 453-454; Daniel Sutherland (ed.), A Very Violent Rebel: The Civil War Diary of Ellen Renshaw House (Knoxville, Tn.: The University of Tennessee Press, 1996), p. 170; John Richard Dennett, The South As It Is, 1865-1866 (Athens: UGA Press, 1965), p. 268; "Condensed History of Atlanta," ACD 1867, p. 33.

(2) Charles B. Boatenreiter, unpublished biography of John Boutelle by his great grandson in the John Boutelle Personality File at the Atlanta History Center Archives; Elizabeth Lyon, Atlanta Architecture: The Victorian Heritage (Atlanta Historical Society, 1976), pp. 11, 15, 18, 94; "John C. Peck Succumbs After A Long Illness," AC, 3/6/1908, p. 5.

(3) Boatenreiter, no pagination; "John C. Peck . . .," AC, 3/6/1908, p. 5; "John C. Peck Dies After Illness of Several Weeks," AJ, 3/6/1908, p. 9. Captured by Sherman's forces in Roswell, Ga., the rifles made by Peck became a curiosity and one was even exhibited at the 1895 Cotton States Exposition.

(4) ACD 1874, p. 184; "Our Wealthy Men," AC, 8/14/1876, p. 1; "John C. Peck . . .," AC, 3/6/1908, p. 5.

(5) H. J. Kimball, International Cotton Exposition Report of the Director-General (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1882), pp. 87, 95, 105; AC, 4/20/1881; AC, 10/5/1881, p. 10; "John C. Peck . . .," AC, 3/6/1908, p. 5.

(6) "John C. Peck Dies . . .," AJ, 3/6/1908, p. 9; "Tribute Paid to John C. Peck," AC, 3/16/1908, p. 16.

(7) ACD 1874, p. 184.

(8) "John C. Peck Dies . . .," AJ, 3/6/1908, p. 9.

Richard Dees Funderburke, Phd

Good job Richard. Well researched and well written....a fitting tribute to one of Atlanta's resurgent leaders.

ReplyDeleteMy favorite building is the customs house. I saw your other post where you said GL Norrman designed Peck's church and was a member. Didn't know there were so many Unitarians in Atlanta.

ReplyDeleteAs usual - excellent article - Peck certainly had his hands in much of Atlanta's New South period - thanks for all you do -

ReplyDelete@Phyllis. Thanks for the comment. The Unitarian congregation was always very small with constant money problems. I imagine that Peck was the wealthiest member and might have bankrolled it. Also, the church had to rely on "support money" from northern churches many years. Thankfully, it has survived until the present day and kept the old records from the very beginning in the 1880s with letters and documents that show how active members like G. L. Norrman were in the early years. It was really nice to those original documents when I was researching the church and Norrman. What a treasure trove!! Nowadays, the church [it is Unitarian/Universalist] also runs a large and very popular private school not too far from where we live.

ReplyDelete@Phyllis. I like the U.S. Customs House too -- looks Venetian Gothic to me but it was designed in the age of John Ruskin so maybe not a surprise. It was not designed by a local -- one of the architects of the federal govt. did it. One of my "research projects," Calvin Fay, was selected to be the local supervising architect but then the Grant administration found out that he was a former Confederate officer who was a zealous Democrat actively antagonistic toward blacks and Reconstruction, so he was dismissed.

ReplyDeleteHiya, I’m really glad I’ve found this information. Nowadays bloggers publish only about gossip and internet stuff and this is really irritating. A good blog with interesting content, this is what I need. Thank you for making this site, and I will be visiting again. Do you do newsletters by email?

ReplyDeleteorganic rice cereal without arsenic