|

| Mrs. J. Carroll Payne and daughter Nan in their elegant Victoria near Cain and Peachtree. Photo courtesy of the Atlanta History Center Archives. |

What would Atlanta be without its automobiles? It is difficult to imagine the city stripped of its millions of cars but that is the way it was back in 1904-05 when the city began vehicle registration and only ninety-nine horseless carriages were legally registered to roam the streets. Ten years later, there were 4,500. (1) The statistical growth was so explosive that in 1909, the first national automibile show held in the South convened in Atlanta and notable automakers like Henry Ford, Ransom Olds, John Willys and many others came to town. Adding even more excitement to the craze, Coca Cola magnate Asa Candler and the Atlanta Automobile Association introduced auto racing when they built a $300,000 racetrack where the Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport now stands. (2)

So when did the motorcar supersede the horse and carriage like that of the Payne ladies pictured above, thus inaugurating the Automobile Age in Atlanta? Statisticians, historians and even sociologists might make a strong case for 1909 but for me, it arrived in February 1913. To be even more precise, it began Wednesday afternoon, February 19th. On that day, John Smith of 124 Auburn Avenue demolished twenty-five carriages, sulkies, broughams, surreys, Victorias and buggies valued originally at $30,000 [about $612,000 in modern dollars] and then burned them in a huge bonfire.

As the writer for the Atlanta Journal commented, "What had been prized luxuries had grown into worn-out relics . . . ." Mr. Smith, who had once manufactured and sold carriages, had recently changed his business over to mortorcars and had plans to build a new three story building on his Auburn Avenue site, just off Peachtree, solely for automobile sales and auto maintenance. The many horse drawn vehicles which the

|

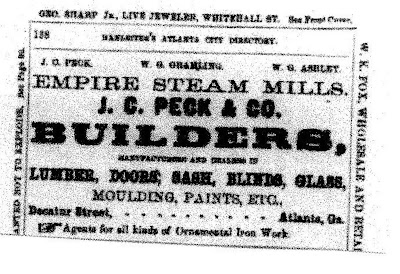

| 1903 City Directory |

|

| Smith's 1914 City Directory ad |

|

| 1913 Newspaper ad for the Cole 50 |

Cole Motor Car Co. of Georgia showroom at 239 Peachtree for $1,985 (about $40,000 in 21st century dollars); the new Cadillac selling for $2,150 at the Steinauer & Wight Co. at 228 Peachtree; or the Overland touring car, a bargain at $985, being shown at the Overland Southern Motor Car Co. at 232 Peachtree. (3) These luxury cars had the additional "luxury" of not requiring expensive horses to feed and maintian.

But let's step back in time for just a moment to 1899 and see how drastic the change was in the first decade of the twentieth century and how the motorcar remade the face of the city. Less than fifteen years before Mr. Smith's bonfire, the city was essentially devoid of the horseless carriage. Transportation was by foot, bicycle, the electric streetcars or by means of horses and mules. Atlanta had nine carriage dealers or

|

| Atlanta City Directory 1903 |

|

| Wagons for hire at the Passenger Depot. Atlanta City Directory 1902 |

|

| Atlanta City Directory, 1903 |

|

| Atlanta City Directory, 1902 |

|

| Atlanta Fire Dept. horses and wagon. Photo courtesy of the Atlanta History Center Archives. |

And don't forget the mansion of Atlanta's elite along Peachtree, Washington Avenue, Capitol Avenue, West Peachtree and other nearby streets with private stables on large or deep lots.

|

| Linnie Condon in Victoria outside the Condon home on Linden near Spring Street. Photo courtesy of the Atlanta History Center Archives |

|

| Atlanta mansion of James W. English with a brougham waiting at the curb (Cone Street). Courtesy of the Atlanta History Center Archives. |

Just imagine the chaos on busy days when the horses, mules, carts, wagons and carriages from all the many stables might pour into the congested streets of Atlanta. By 1903, the city had a population of 96,550 in a small eleven square miles and only 63.4 miles of paved streets out of a total of 200.4 miles of roadways (meaning 68.36% were dusty, muddy unpaved roads). (5) Amid this chaos and dirt created by all these vehicles and animals on the unpaved streets, which were anathema to motorcar drivers, there were the added hordes of pedestrians, clanging streetcars carrying up to 71,403,000 passengers yearly by 1913, and intrepid bicycle riders (in 1899, there were 22 bicycle dealers and repairers in the city). (6) Furthermore, on any given day, horse/mule powered vehicles entered the city from outlying areas and competed for space with the hometown traffic.

By the year of the bonfire,however, the means of personal and business transportation had drastically changed. The streetcars still ran with ever increasing numbers of passengers but motorized vehicles were taking over. The first local advertisement for a horseless carriage that this author could find appeared in 1902 for the Locomobile "agency" of H. M. Ashe, whose primary business was the sale of typewriters at the

|

| Atlanta City Directory, 1902 |

Other businesses were buying trucks to replace work and delivery wagons. Johnson Motor Co., on S. Forsyth Street advertised their Chase Trucks priced from $900 to $1,250 and available in six models with load capacities from 500 to 4,000 pounds. The dealer claimed that these trucks "Lead all [in] Simplicity and Economy" and that large local businesses like Foote & Davies [printers], the Nunnally Co., [candy manufacturer], C. H. Merckel Co. [grocer], and Phillips & Crew [piano and music sales] had already

|

| 1913 newspaper ad for Chase Trucks |

manufacturer of trucks in the mix by 1913. Long-time Atlantan Edward Van Winkle, who made his original fortune as a manufacturer of cotton gins and textile machinery, started a new business in 1912. His trucks were advertised as "Made in Atlanta."

If you couldn't afford a car or a truck, there was the more affordable option of the new Indian motorcycles at Hendee Manufacturing Co. (437 Peachtree Street) for $200 to $250 (between

|

| Atlanta City Directory |

$4,000 and $5,000 in more modern dollars). They were guaranteed to "Take you there and back again at from 4 to 50 miles an hour" and were perfect for "business or pleasure." You could even get an "Indian Maid" sidecar to carry a passenger. (7)

|

| 1913 Atlanta newspaper ad for the Indian motorcycle |

When the city directory of 1914 came out listing local businesses as of 1913, the changes from

1899 were little short of amazing. There were now more than ten pages of advertisements and listings for automobiles, trucks and related services and accessories. Carriage makers and/or dealers had dropped from fifteen to three and one of those was not in Atlanta but East Point, Georgia. Of the two remaining carriage dealers listed, one was John Smith who we know had already switched to motorcars. In fact, he had a full page ad [see above] in the directory for his high end vehicles like the Chalmers ($2,250.00 to $3,750.00) and the Pierce-Arrow, which sold from $4,425.00 up to a whopping $7,200 (almost $147,000 today). (8)

Other listings in 1914 show additional significant changes. The livery stables, which had once clustered around Five Points, were gone. Wagon makers were halved (six down to three) and the six wagon yards of 1899 were reduced to two. Those dealing in harnesses and harness repair had dropped from fifteen to seven. There were still forty-five blacksmiths in town but it is probable that many of these were also working on automobiles or ironwork not related to either automobiles or carriages. At least one of these blacksmiths announced in the directory that he was an expert in repairing the new automobile. (9)

Capital investment related to the booming automobile industry was also expanding, along with the funding for more paved streets demanded by the influential "automobilists." New buildings and businesses proliferated, especially on Peachtree from Ellis Street to Ponce de Leon Avenue. Automobile or automobile related firms located on the city's most prestigious thoroughfare jumped from zero in 1909 to thirty-three in 1914. These were not all greasy garages either. In February 1913, a five story Buick dealership with grand columns, an elegant entrance awning, decorative cornice and masses of plate glass windows opened at 241-243 Peachtree (corner of Peachtree and Harris streets). It had been designed by Walter Downing, one of the

|

| New 1913 Buick dealership. |

as well . . . ." (10)

As the second and third decades of the twentieth century progressed, the expansion of automobile businesses and a huge increase in vehicles themselves essentially ended the old urban reliance on the horse and mule. (11) What had begun in the earliest years of the twentieth century when a few primitive Locomobiles put-putted along Atlanta's largely unpaved streets had completely changed as the horseless carriage remade the look, feel and even smells of the city within a shockingly short time span. As our journalist of 1913 stated in his article about John Smith's bonfire, it was the "automobile in which fashion rides today." Into Mr. Smith's planned conflagration of "crackling fire" went a way of life and transport centered on animal power. The artifacts destroyed that winter day in 1913 included the odd three wheel vehicle of Dr. Thurmond with his "upholstered chair" mounted behind a high dashboard, the "special trotting sulkey [sic]" of Joe Kingsberry, John Hill's Victoria, the spider phaeton of Wilmer Moore (see below), and Mrs. Hunter Smith's brougham. Also into the blaze went the old carriage of former governor

|

| Wilmer and Cornelia Moore in their Spider Phaeton [with unknown servant] when it was brand new. Photo courtesy of the Atlanta History Center archives. |

Richard Dees Funderburke, Phd.

_____________________

As always, I extend very special thanks to the wonderful archivists at the Atlanta History Center for all their help and generosity in allowing me to use a few of the facility's outstanding collection of photographs.

(1) Howard Preston, Automobile Age Atlanta, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1979, p. 50 (Hereafter Preston).

(2) Preston, p. 17 & pp. 27-28.

(3) Atlanta Journal (Hereafter AJ), 2/20/1913, p. 11; Atlanta Constitution (Hereafter AC), 2/23/1913, p. 10; AC, 2/16/1913, p. 12.

(4) Atlanta City Directory 1899 (Hereafter ACD), pp. 1388-1397, 1432-1432, 1448, 1485-1486, 1493, 8.

(5) Preston, pp. 10 & 13.

(6) Preston, p. 48; ACD 1899, p. 1387 (for bicycle dealers).

(7) ACD 1902, p. 176 (Locomobile ad); AJ, 2/2/1913, p. H; AC, 2/23/1913, p. 2-A; ACD 1914, p. 22 (Van Winkle truck ad), p. 6 (Piedmont Laundry), p. 1857 (Belle Isle); AC, 3/3/1913, p. 13-B ( Barclay & Brandon Funeral Home ad); AJ, 11/9/1913, p. L.

(8) ACD 1914, pp. 1716-1719, 1797, 5 (John Smith ad).

(9) ACD 1914, pp. 1725, 1777, 1776, 1797, 1801, 1854.

(10) Preston, p. 37; "Buick's New Home To Be Opened Next Tuesday," AJ, 2/20/1913, p. 11.

(11) Preston, pp. 37-38 & 51; AJ, 2/20/1913, p. 11.

(12) ACD 1902, p. 176; AJ, 2/20/1913, p. 11.